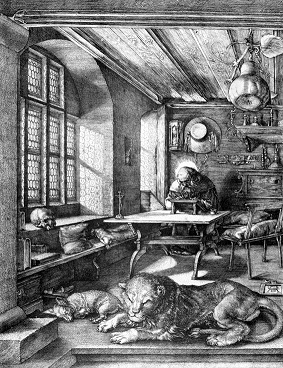

We talk a lot about virtues in Masonry, and for good reason. As the school of positive psychology persuasively argues, human beings fulfill more of their potentials and dreams by focusing more of their attention and energy on their strengths and the good that they desire to do. Even so, there is folly in ignoring our weaknesses or our potentials for doing harm. It can also be true that we fool ourselves by hiding vices behind the masks of virtues, and that is often nowhere more tempting and troublesome than in those parts of our lives we label as “spiritual.” This article will chip away a little on such issues for those of us on a contemplative journey in Masonry.

These matters take us right back to the Entered Apprentice degree and the lesson about perfecting the rough ashlar, which requires that we be ready, willing, and able to identify our vices. Unfortunately, however, it isn’t always easy to discern our vices. As previously noted, sometimes we can convince ourselves that they are actually virtues. Compounding this potential for self-deception is the fact that we don’t always have conscious awareness of everything occurring in our psyches.

Furthermore, in one set of circumstances it may be virtuous to think and act in a particular way, while in another situation such thinking and behavior would be more an expression of our vices and superfluities. These are among the reasons why it may be useful to regard self-awareness as our first contemplative practice, the first virtue to employ and enhance. Scottish Rite Masons should recall that in the Fourth Degree, when we are told we are ascending “into the skies of spiritual knowledge,” we are given the Key to the Mysteries, which is further explained as the key of self-awareness (Know Thyself!).

Self-awareness and discernment demand, in part, that we ask ourselves, “Why? Why am I thinking what I’m thinking? Why am I doing what I’m doing?” In doing so, it’s helpful to not settle for the first answers that come up. We can probe more deeply and courageously by asking: “Why do I want what I want, which is to say, what are all my motives and my intentions? What could be the worst of them? What might I be most ashamed to admit?”

Examining, evaluating, and intentionally changing this inner tapestry — motives, intentions, vices, and virtues – is something we must do for ourselves, although others can be of assistance in different ways. So I offer you some of the deceptive vices I and others have discovered in asking ourselves such questions, specifically with regard to our interests and efforts in contemplative practice. I’ll start with two basic ones, and then I’ll present several that involve those two in more complex ways. As you will no doubt see, all these vices can have countless intersections with each other.

Basic Vices for Contemplatives

Hypocrisy: choosing to appear more virtuous, principled, or adherent to some belief, value, or practice than I actually am, such as self-righteously criticizing others for vices that I also have.

Spiritual Pride: attitudes of arrogance, conceit, self-righteousness, or vanity based on the conviction that my beliefs, values, or practices make me superior to others in one or more ways.

More Complex Vices for Contemplatives

False Humility: denying my own worth, strengths, or accomplishments, or otherwise assuming an inauthentic appearance of being meek, lowly, or servile; a pretense often motivated by the fear of seeming prideful and therefore being judged as hypocritical.

Spiritual Materialism: shoring up my spiritual pride by collecting things as evidence to myself and others of being more sophisticated, advanced, or praiseworthy; such things may include artworks, books, concepts, historical knowledge, jargon, degrees, titles, honors, positions, vows, practices, spiritual experiences, ‘gurus,’ students, disciples, etc.

False Asceticism: adopting forms of austerity, abstinence, and fasting, or appearing to do so, for the purposes of seeming more holy, enlightened, or pious to myself or others.

False Benevolence: a pretense of being kinder, more caring, more compassionate, or more charitable than I am genuinely motivated to behave, in the attempt to totally conceal my actual hostility, selfishness, or even disinterestedness.

False Equanimity: giving the appearance of rarely if ever having strong reactions to or feelings about things, rarely if ever being stressed, worried, angry, hurt, passionate or even delighted; this is a psychosocial strategy that requires minimizing and compartmentalizing the emotional aspects of being because they are regarded as too dangerous.

Acedia: an air of apathy, ennui, or boredom with ordinary matters, as if I am simply beyond the mundane silliness that disturbs other people, while in fact I am avoiding coping with realities that disturb me in some way.

Romantic Bliss: a euphoric affectation of extreme positivity, optimism, happiness, or contentment worn as a mask over my feelings of dissatisfaction, disappointment, pessimism, frustration, and hopelessness. The term 'romantic' is used in the sense of "marked by the imaginative or emotional appeal of what is heroic, adventurous, remote, mysterious, or idealized." (see Merriam-Webster.com)

Romantic Despair: a dramatic affectation of hopelessness, pointlessness, pessimism, or defeatism, involving a disaffection with life for failing to be congruent with my ideas about the way it should be; similar to acedia in its avoidance of actually trying to cope more effectively with life.

Romantic Rage: a bitter affectation of loathing, hatred, and ill will toward various aspects of life, including other people, for failing to match my ideas about how they should be; another vice of avoidance.

This is far from a complete list, but is perhaps a worthwhile starting place for anyone interested in contemplatively wielding the gavel. As we do so, we may discover other vices that are very common, including a self-loathing that keeps us stuck in negativity and at war with ourselves. Such self-loathing is often rooted in the fear that we cannot satisfy our idealized notions of perfection or of being acceptable and admirable to others. We may even mistakenly consider such desires as detestable in themselves.

Of course, as we discover vices in ourselves, we naturally ask what we can do about them. One fundamental answer is that it’s helpful to simply be more honest and accepting about what it means to be human, which in turns enables us to exercise more self-compassion and genuine self-nurturance. These inner developments naturally facilitate us becoming more authentically virtuous people, reflecting our healthy self-love in the ways we become more loving with others.

Finally, I want to avoid giving the impression that these processes are merely a formula of personal development that’s entirely within our conscious control. As we earlier considered, we don’t have immediate conscious access to everything in our souls. We will miscalculate, misunderstand, and make mistakes because, to some extent, we are always mysteries to ourselves. To acknowledge that fact is an important part of accepting our humanity. Ultimately, contemplative practices such as this are about penetrating into the deepest mysteries of our being with a sense of adventure, experiencing the joys of spiritual discovery and creativity. Wielding the gavel may thus become more of an ongoing artistic experiment than a painfully arduous labor toward an unattainable completion.

________________________________________

THANK YOU FOR READING THE LAUDABLE PURSUIT!

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PIECE, PLEASE FEEL FREE TO SHARE IT ON SOCIAL MEDIA SITES AND WITH YOUR LODGE.

For more information on Bro. Chuck Dunning: CLICK HERE

Chuck Dunning has authored: Contemplative Masonry: Basic Applications of Mindfulness, Meditation, and Imagery for the Craft

Also, visit us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TheLaudablePursuit

________________________________________

SHOW YOUR SUPPORT

If you enjoyed this content, you can show your support by visiting the our Bookstore, or by donating below: